The recommendation below is an advertisement. Most of the links here are part of Amazon's affiliate program (unless otherwise stated), which helps support this website. It's also more than that - it's a hand-picked recommendation of something I've used myself. If you're interested,

here is a full list.

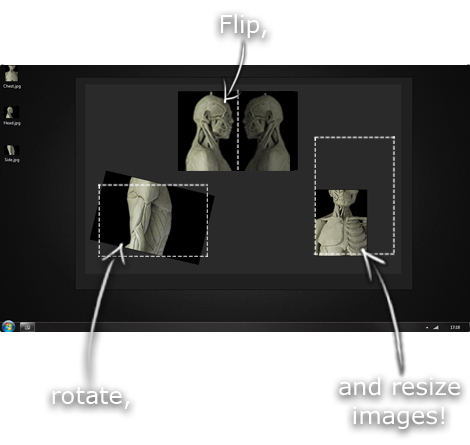

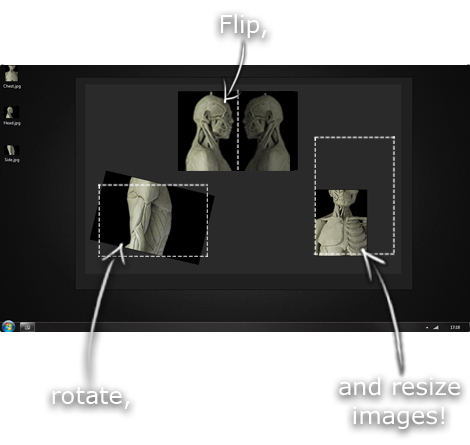

PureRef

This is another one of those things that aren't sold through Amazon, so I don't get a commission on it - but it's just too good to leave out. PureRef is a fantastic piece of software that is both Windows and Mac compatible. It's used for collecting reference and compiling them into a moodboard. You can move them around freely, have them automatically arranged, zoom in/out and even scale/flip/rotate images as you please. If needed, you can also add little text notes.

When starting on a project, I'll often open it up and start dragging reference images off the internet onto the board. When I'm done, I'll save out a '.pur' file, which embeds all the images. They can get pretty big, but are way more convenient than hauling around folders full of separate images.

Did I mention you can get it for free? The developer allows you to pay whatever amount you want for it. They recommend $5, but they'll allow you to take it for nothing. Really though, with software this versatile and polished, you really should throw them a few bucks if you pick it up. It's more than worth it.