8:33 PM, Wednesday May 11th 2022

If you have questions you're more than welcome to ask them.

Asking them directly instead of asking to ask would save time though.

If you have questions you're more than welcome to ask them.

Asking them directly instead of asking to ask would save time though.

Hi,

I understand. I've returned to the assignment but I still have issues with the Y axis, while the X and Z axis are more often converging in sets. As for drawing larger, I do find that difficult to do on the A4 paper so I'm switching to a sketchpad. However, I feel frustrated because I'm not interpreting something correctly. Is there an even easier way to explain the vanishing point placement and how to get the lines to converge accurately? I'm stumped and stuck. Thanks!

Generally speaking an A4 page should provide ample space for 5-6 boxes (it's entirely fine for the line extensions to overlap so don't worry about that) but if for whatever reason you feel more comfortable working on bigger paper, that's fine.

As to your question, there's two ways I think this can be interpreted:

What can I do to make my lines converge more accurately each time, without making mistakes

or What can I do to improve their convergences

I'll answer both. To the first, unfortunately I don't have an entirely satisfactory answer, because the challenge is essentially designed to have you improve by making mistakes, identifying those mistakes, and then adjusting your approach bit by bit over the course of 250 boxes. So in that sense, this interpretation of the question is about eliminating the mistakes before the boxes are drawn, and the mistakes are very much part of what help us improve. Or at least, the analysis of the nature of those mistakes, by extending our lines out.

To the second interpretation, we get into the actual meat of it. If we have 4 lines on a page, like the 4 edges of any given set (of the box's 3 sets of parallel edges) as shown here, we can kind of see that they do not converge all at one point already, but we can demonstrate this further by extending the lines out. Those top two lines converge way too quickly, suggesting that the second from the top should be slanting down and to the left more, and similarly the bottom two lines converge a little too quickly, and the third line down should be slanting up and to the left a bit.

Hindsight is 20-20, after all - we can tell all these things after the fact, once the lines are already drawn. But what can we do while we're drawing the lines in the first place? Well, we have to think about all four lines simultaneously. Some of those four will have been drawn, while others will have yet to be drawn. And thus, some are set in stone, and others are not.

The Y method process establishes 1 line in each set, leaving 3 yet to be drawn in each set. This doesn't give us enough information to establish where the vanishing points are. This doesn't mean that there is a secret vanishing point that we must "discover" somehow - it means that no vanishing point has been established, and so there are a lot of possibly "correct" vanishing points we can end up using. The one edge we have for each set merely points towards its own vanishing point, but it does not tell us where along its trajectory that vanishing point may fall.

So, you can think of it as though 1 edge is set in stone, unchanging, and the other 3 are still kind of free-spinning, so to speak. It isn't until you add the second edge that the vanishing point is actually defined, because that second edge will point to the location along the first edge's trajectory where the vanishing point will lie, as shown here. Any two lines, if they're not parallel to one another on the page, will converge and intersect in some direction, and at some point.

Once these two lines have been drawn (and thus two lines in the set are still as yet undefined), we can now think about how the remaining lines need to be aligned in order to converge towards that same far off point. Of course since we don't have those line extensions at this stage in the process, we have use the shorter lines we have drawn to infer this information, to visualize how they're going to converge.

This is not easy, and you will make mistakes. Also, you will find that as you progress through constructing the whole box, that discrepancies in some of these convergences will actually throw off the "back corner" of the box. Students often get frustrated with this, focusing their attention on fixing the back corner, when it is in fact a symptom of the convergences. It's a red herring, a distraction - it causes they to focus their attention away from the convergences, and so the problems get worse.

Long story short, you have to consciously think about all four of these lines, and how they're behaving as you draw them, in order to have them converge more consistently. One thing that can help with this is leveraging the fact that as part of the ghosting method, we put down start/end points for each line. We can do this for multiple lines at a time, laying down little points to kind of figure out how the lines might meet at the box's corners, but without committing ourselves. While a whole line should not be redrawn or corrected (because it's already a decision that's been made, and it's impossible to ignore in the drawing), a tiny point is less strict. You can see here how ScyllaStew lays down the points for several lines before deciding on how to draw a given edge.

I hope that helps - but ultimately, it may not help as much as you will have liked. Reason being, the bulk of the improvement is going to come from going through the instructions and the material provided as best you can, so you can follow the procedure correctly (applying the Y method, ensuring that you're extending the lines in the right direction, etc.) but given that, the rest of it will improve with practice and experience, from actually tackling the problems and allowing yourself to make mistakes, then analyzing those mistakes and continuing forward.

Unfortunately what kept that from happening the first time around was the fact that you didn't extend many of the lines correctly, making the analysis considerably less useful in identifying your mistakes.

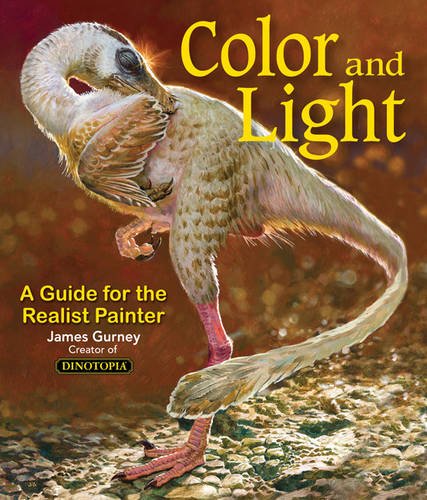

Some of you may remember James Gurney's breathtaking work in the Dinotopia series. This is easily my favourite book on the topic of colour and light, and comes highly recommended by any artist worth their salt. While it speaks from the perspective of a traditional painter, the information in this book is invaluable for work in any medium.

This website uses cookies. You can read more about what we do with them, read our privacy policy.