The recommendation below is an advertisement. Most of the links here are part of Amazon's affiliate program (unless otherwise stated), which helps support this website. It's also more than that - it's a hand-picked recommendation of something I've used myself. If you're interested,

here is a full list.

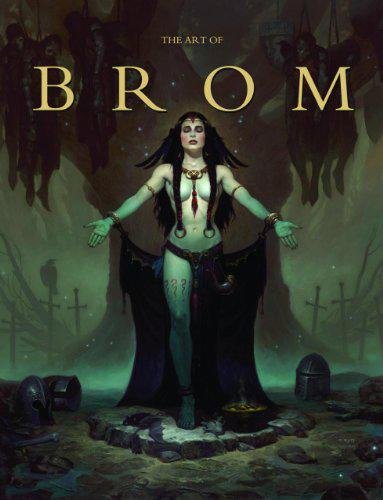

The Art of Brom

Here we're getting into the subjective - Gerald Brom is one of my favourite artists (and a pretty fantastic novelist!). That said, if I recommended art books just for the beautiful images contained therein, my list of recommendations would be miles long.

The reason this book is close to my heart is because of its introduction, where Brom goes explains in detail just how he went from being an army brat to one of the most highly respected dark fantasy artists in the world today. I believe that one's work is flavoured by their life's experiences, and discovering the roots from which other artists hail can help give one perspective on their own beginnings, and perhaps their eventual destination as well.