This website uses cookies. You can read more about what we do with them, read our privacy policy.

3:10 AM, Friday April 2nd 2021

Alrighty! So throughout this set, you've got some really good, and are generally moving in the right direction, but you've also got some blunders that we can address, and help set to rights.

Starting with the organic intersections, I have a couple things to call out:

-

Remember that this exercise is all about designing the silhouette of a given sausage form based on the forms it's going to be resting upon, taking gravity into consideration. This basically means that we don't draw a form, then figure out how it's going to interact with the rest of the pile - we have to actually factor that pile into how the form itself is drawn. On this page you've got a couple sausages along the top that don't quite hold to this - it looks like you may not have been entirely paying attention, and then caught yourself halfway through, and tried to sort things out.

-

On the second page, you end up kind of blurring the line between cast shadow and line weight. It's really important that you remember the difference between them. Line weight can cling to the silhouette of a form, but must always be kept subtle - avoid making it really thick and obnoxious. It is also intended for a specific purpose, to clarify specific overlaps, and should only be added in specific localized areas, rather than all the way around a form. Cast shadows on the other hand can't cling to the silhouette of a form - they must be cast upon other surfaces, and must respect a consistent light source. They can however be as thick/broad as you want them to.

Moving onto your animal constructions, I definitely think there's a lot of points of strength here, as well as a fair bit of improvement over the set. There are many well built examples of head construction, like in your hyenas, where in the top and left side drawings you established how the eye socket and muzzle all wedge together tightly, creating a stronger division of planes. There are however cases where you throw these core principles entirely to the wind - like in this rhino drawing where you ended up completely ignoring the core principles of head construction. Now, rhinos can be really tricky to wrap your head around, so I assume that happened because you were somewhat overwhelmed with the problem - although I suspect the fact that you intended to get into detail could have also played a role, as many students tend to approach construction differently when they know they're going to get into detail. The intent to do so can distract us from pinning that construction down using the tactics we generally do know.

Since I do have a demo I put together for another student on how one might apply construction to a rhino head, I'll go ahead and share it with you - though from what I've seen of your work, you do more or less understand this already. The key distinction is this: sometimes you put lots of time and focus into a task, and sometimes you don't. Sometimes you rush, and it impacts your work negatively, because what we're doing here involves a lot of very conscious problem solving.

One key element to construction is that the individual components we add to our structures need to be as simple as possible - with no unnecessary complexity to their silhouette - so they can maintain the illusion of solidity. If you draw a random blob on the page, it's not necessarily going to read as being three dimensional. That doesn't mean there can't be complexity to the silhouette - just that the complexity needs to make sense.

If you take a look at this cougar drawing, you've got a really wobbly, arbitrary blob attached to its belly, and it feels entirely flat because of the complexity to it. Instead, there are a number of things that should have been done differently, which I point out here directly on your drawing.

The key point is about ensuring that your additional masses should concentrate their complexity where it establishes the relationship between that mass and the existing structure. One thing that helps with the shape here is to think about how the mass would behave when existing first in the void of empty space, on its own. It all comes down to the silhouette of the mass - here, with nothing else to touch it, our mass would exist like a soft ball of meat or clay, made up only of outward curves. A simple circle for a silhouette.

Then, as it presses against an existing structure, the silhouette starts to get more complex. It forms inward curves wherever it makes contact, responding directly to the forms that are present. The silhouette is never random, of course - always changing in response to clear, defined structure. You can see this demonstrated in this diagram.

Overusing contour lines is a really common mistake, especially when students realize their additional mass doesn't feel solid at all. For example, here on the hyena's back. While properly drawn contour lines can make a form feel more 3D and solid, it's only in isolation - it won't make the form feel like it wraps around the existing structure any better, and won't define its relationship with that structure. That can only be achieved through proper, intentional design of the silhouette. So take your time.

This "designing" of your additional masses applies across the board - including the smaller masses that form along the legs. You can see this in this dog leg example - not also just how much I can build upon that basic sausage structure. Often times sticking with a basic sausage structure (simple sausages all the way down) and then building up additional bulk is the way to go, with a whole structure of these masses all interconnecting, rather than slapping the odd additional mass as a one-off.

So, I've shared a few things for you to work on. I'm going to assign some additional pages of drawings below. I do think you're moving in the right direction, but you need to slow down to apply yourself more effectively. That's both in taking the time to figure out how to design your shapes more purposefully, as well as to take more time to observe your reference carefully and frequently (to ensure you don't end up working from memory).

Next Steps:

Please submit 3 additional pages of animal constructions. Don't be afraid to draw bigger - you don't have to cram lots of drawings in each page, and drawing bigger can often help explore smaller elements - like eyes/eyelids - more effectively.

6:27 PM, Friday April 2nd 2021

Dont be alarmed at how fast im replying. I really went through all your notes and took my time on these.

thank you so much for your attention to detail on these. i finally am understanding sausage legs first, then add form.

face perspective is still a bit wonky but overall im understanding the puzzle better.

7:21 PM, Monday April 5th 2021

These are looking much better, and do improve as you progressed through the set. There is of course still room for improvement, but that'll come with continued practice - what matters most is that you're demonstrating a growing understanding of the concepts, and that you're practicing the right things to continue getting better.

One small observation - your rhino's eye socket is floating loosely there, so the head construction doesn't feel quite as solid as it could. Still not bad, but the eye socket establishing that puzzle is integral.

I'll go ahead and mark this lesson as complete.

Next Steps:

Feel free to move onto the 250 cylinder challenge, which is a prerequisite for lesson 6.

8:27 PM, Monday April 5th 2021

Ok thank you.

FYI, i started watching those 1994 perspective lectures. Awesome resource. Hopefully will be something that helps me in these future lessons.

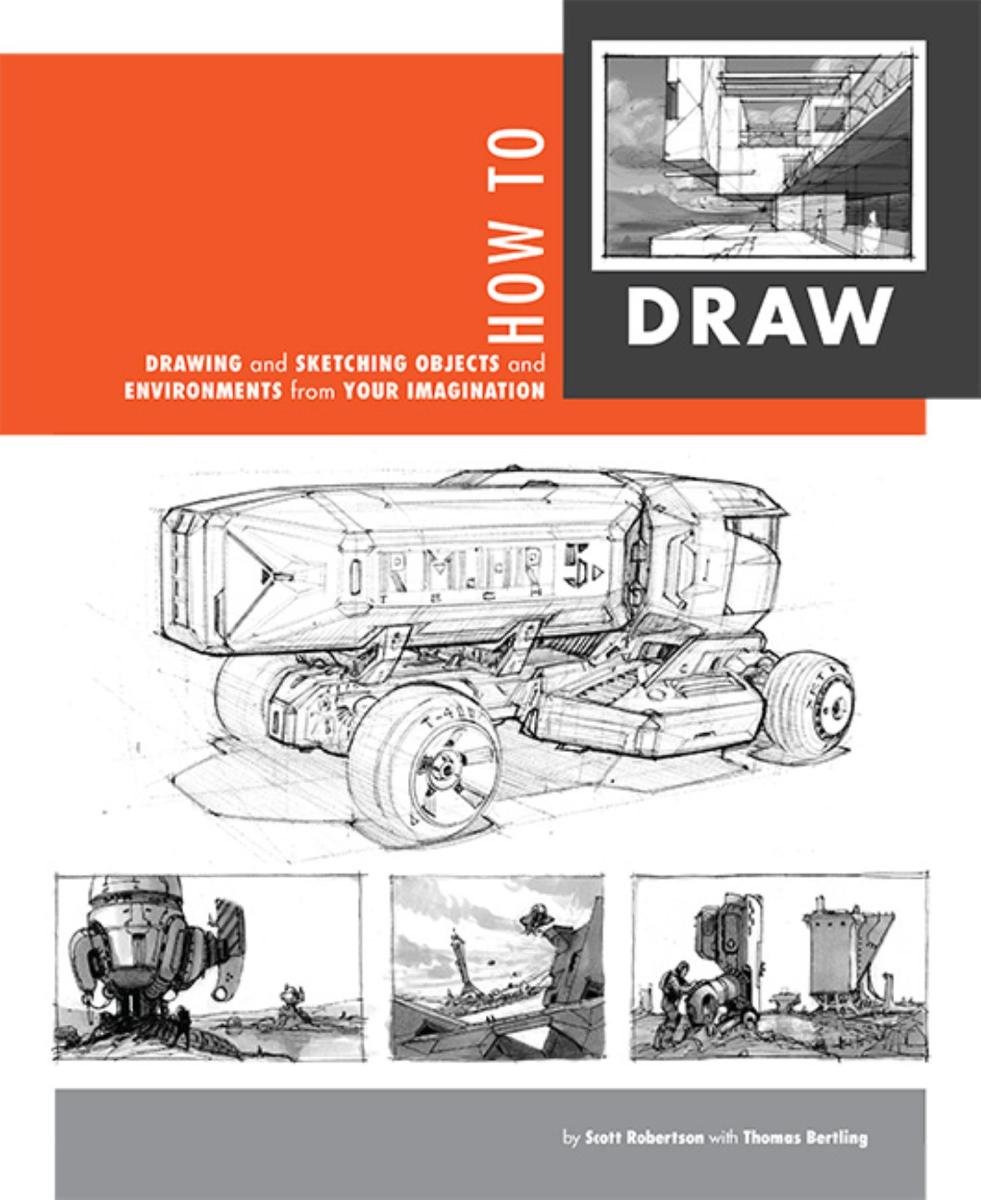

How to Draw by Scott Robertson

When it comes to technical drawing, there's no one better than Scott Robertson. I regularly use this book as a reference when eyeballing my perspective just won't cut it anymore. Need to figure out exactly how to rotate an object in 3D space? How to project a shape in perspective? Look no further.