Lesson 4: Applying Construction to Insects and Arachnids

6:25 AM, Thursday December 2nd 2021

Hello, this is my submission for the Lesson 4 homework.

Jumping right in with your organic forms with contour curves, throughout many of these you're doing a really good job of maintaining the characteristics of simple sausages - although keep an eye on cases where one end gets either smaller than the other, or pointier/more stretched out. Always strive for ends that are circular in shape, and equal in size. Additionally, keep an eye on the degree of your contour curves - remember that as discussed in Lesson 1's ellipses video, the degree of these cross-sectional slices will get wider as you slide away from the viewer.

And, a couple additional points:

Do not leave out the central minor axis line. Always be sure to follow every step from the instructions.

Be sure to draw through the ellipses at the tips two full times before lifting your pen - as goes for all ellipses you freehand.

Continuing onto your insect constructions, overall you're doing really quite well. I can see that you're clearly going to considerable lengths to adhere to the core principles of construction, building everything up piece by piece, without jumping ahead too far, or trying to solve too many problems all at once. There are a few things I want to call out though, to help ensure that you stay on the right track, and continue to get the most out of each of these exercises.

To that point, they are exercises. While we're drawing real, existing things, and doing so from a reference image, the goal is not to reproduce the reference perfectly, but rather to use that reference as a source of information as we gradually build up what is effectively a three dimensional spatial puzzle. It's almost a game - as we attach each new piece, we're gradually working towards that target from the reference, but every new piece also gives us more to ultimately contend with - more thickness here, more volume there. Sometimes a single decision may simultaneously push us closer, and farther away, from our target.

At the end of the day, it's the act of building up these forms, of considering how they relate to one another in 3D space (rather than just on the 2D space of the page), which is what we're aiming to achieve. And, in many cases you've held to that very well - but not every case. While it's far less prevalent in your work than it is in some other students', there are still cases where you'll jump back and forth between building up in 3D space, and taking shortcuts that only a 2D drawing would allow.

Because we're drawing on a flat piece of paper, we have a lot of freedom to make whatever marks we choose - it just so happens that the majority of those marks will contradict the illusion you're trying to create and remind the viewer that they're just looking at a series of lines on a flat piece of paper. In order to avoid this and stick only to the marks that reinforce the illusion we're creating, we can force ourselves to adhere to certain rules as we build up our constructions. Rules that respect the solidity of our construction.

For example - once you've put a form down on the page, do not attempt to alter its silhouette. Its silhouette is just a shape on the page which represents the form we're drawing, but its connection to that form is entirely based on its current shape. If you change that shape, you won't alter the form it represents - you'll just break the connection, leaving yourself with a flat shape. We can see this most easily in this example of what happens when we cut back into the silhouette of a form.

As shown here, in red I've marked out where you cut into the silhouette of those previously solid, 3D, complete and enclosed forms, and in blue where you've extended off a 3D form, but only using a partial, 2D shape.

Instead, whenever we want to build upon our construction or change something, we can do so by introducing new 3D forms to the structure, and by establishing how those forms either connect or relate to what's already present in our 3D scene. We can do this either by defining the intersection between them with contour lines (like in lesson 2's form intersections exercise), or by wrapping the silhouette of the new form around the existing structure as shown here.

You can see this in practice in this beetle horn demo, as well as in this ant head demo. This is all part of accepting that everything we draw is 3D, and therefore needs to be treated as such in order for the viewer to believe in that lie.

Now I really do mean it when I say that for the most part, you're doing a good job of adhering to the kind of approach demonstrated in the shrimp and the lobster demos from the informal demos page (which, being my most recent demos, are also the best depiction of this kind of strict regard for keeping everything 3D).

Continuing on, I noticed that you seem to have employed a lot of different strategies for capturing the legs of your insects. It's not uncommon for students to be aware of the sausage method as introduced here, but to decide that the legs they're looking at don't actually seem to look like a chain of sausages, so they use some other strategy.

In your case in particular, I think you are largely thinking about the sausage method, but not as strictly as you ought to. As a result, there are plenty of places where you're missing the contour lines that define the intersection/joint between the sausage segments, and others where you only opt to draw a sausage form partially, leaving it open-ended where it overlaps the previous one. Additionally, in a few cases - like this ant, you also deviate from the characteristics of simple sausages.

The key to keep in mind here is that the sausage method is not about capturing the legs precisely as they are - it is about laying in a base structure or armature that captures both the solidity and the gestural flow of a limb in equal measure, where the majority of other techniques lean too far to one side, either looking solid and stiff or gestural but flat. Once in place, we can then build on top of this base structure with more additional forms as shown here, here, in this ant leg, and even here in the context of a dog's leg (because this technique is still to be used throughout the next lesson as well).

Lastly, a quick point about the use of line weight. I'm noticing a lot of places where you're applying line weight to generally reinforce or re-commit to the overal silhouettes of your forms. Instead, I'd strongly recommend using your line weight in a more limited fashion - focusing its use specifically on clarifying how specific forms overlap one another, limited to the localized areas where those overlaps occur, as shown here with this example of two overlapping leaves. Additionally, strive to keep your line weight subtle, like a whisper to the viewer's subconscious.

Cast shadows, on the other hand, which are a different tool than line weight (though often confused with it), are subject to different restrictions. Cast shadows can be as broad as we want, but their shape has to be designed to specifically convey the relationship between the specific form casting it, and the surface receiving it - also meaning that they must have a surface to receive them and cannot just float arbitrarily along the silhouette of the form doing the casting. When it comes to the use of filled areas of black, try to reserve these strictly for cast shadows, and avoid using them to capture anything else - be it form shading, or the local surface colour (like where in the ant, you filled the eye in with black). Try to treat the objects like they're covered in the same white, because we simply don't have the breadth of tools we'd need to capture that aspect of our constructions. Here, we're focusing entirely on conveying that which exists in 3D space.

I've called out a number of things, but as a whole you're still doing a great job. These things can all continue to be worked on as you move into the next lesson, so I'll go ahead and mark this one as complete. Keep up the good work.

Next Steps:

Feel free to move onto lesson 5.

Thank you very much for the detailed reply!

This recommendation is really just for those of you who've reached lesson 6 and onwards.

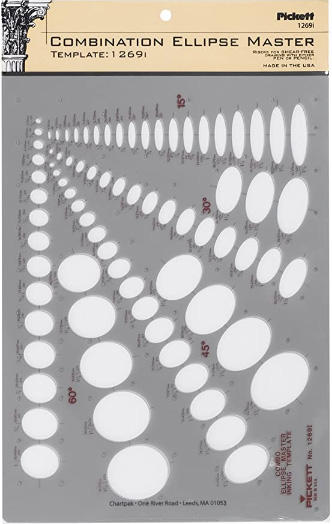

I haven't found the actual brand you buy to matter much, so you may want to shop around. This one is a "master" template, which will give you a broad range of ellipse degrees and sizes (this one ranges between 0.25 inches and 1.5 inches), and is a good place to start. You may end up finding that this range limits the kinds of ellipses you draw, forcing you to work within those bounds, but it may still be worth it as full sets of ellipse guides can run you quite a bit more, simply due to the sizes and degrees that need to be covered.

No matter which brand of ellipse guide you decide to pick up, make sure they have little markings for the minor axes.

This website uses cookies. You can read more about what we do with them, read our privacy policy.