This website uses cookies. You can read more about what we do with them, read our privacy policy.

9:07 PM, Friday July 8th 2022

Overall your work here is quite well done, and while I have a number of things I'm going to call out in order to help you continue making the most out of these exercises, you are by and large doing a good job of building up structures that feel fairly solid and believable.

That said, the biggest concern that I have right now is actually one that can be fixed simply by paying a little more attention to how you go about putting marks down on the page. In that sense, it's a very easy fix. It comes down to the tendency you have to put some marks down more carelessly - often going back over the same stroke multiple times, and not entirely adhering to the core principles of markmaking from Lesson 1, and the specific process of the ghosting method.

There are a ton of careful, considered, and confident strokes throughout your work, so I can see full well that you're entirely capable of this. It's just that sometimes you get a little distracted, and so your focus wanes. This results in more haphazard markmaking, as we can see it here and here. I see it happening more often with smaller marks (so you may simply not be giving them as much time/attention as they individually require, to properly work through the planning and preparation phases before putting those marks down on the page). So, to put it simply - don't let yourself off the hook. Every mark you put down needs to be carefully considered, in terms of what its purpose is, how it can be best executed to achieve that goal, and so on.

To that same kind of point, while I'm largely quite pleased with how you're approaching many of your additional masses (you're clearly putting a lot of thought into the design of each mass's silhouette, considering the specific placement of inward curves, outward curves, sharper corners and more gradual, rounded ones), I can see that you have the habit of placing contour lines onto these masses. This is actually something that is present in the intro video, but more recently I've found that it's really not super helpful in terms of making the additional mass feel solid and 3D, and worse still, for some students it can actually do more harm than good.

Basically it comes down to this - the manner in which a mass that wraps around an existing structure conveys its own solidity as well as its relationship with the existing structure all comes down to its silhouette's design (as discussed in the previous paragraph). If the silhouette was drawn correctly, then it should be able to stand on its own, so no other contour lines are necessary. If however the silhouette was drawn incorrectly, it'll end up feeling flat, like a shape pasted onto the drawing rather than a form actually integrating with it in 3D space. A contour line added to it will not be enough to fix this. It may make the form feel as though it has volume, but the relationship with the existing structure won't be there, so it'll look off.

Now this part isn't something you're doing, but it is a good reason not to include those unnecessary contour lines at all - a lot of students can, without realizing it, slip into the habit of taking less care with those silhouette designs, because they get used to the idea that they can be fixed afterwards with a contour line - even though this fix doesn't actually work. So, they shift from putting their time towards the silhouette design, to just putting whatever down and trying to resolve it after the fact.

So, to put it simply, best something to avoid.

Continuing on, I'm pleased to see that you are generally making good use of the sausage method when constructing your animals' legs, and that you're building up additional masses there as well. One suggestion I do have however is not to only focus on the masses that are going to impact the silhouette. This leaves them floating more on their own, and additional masses benefit immensely from being part of a larger group of forms all pressing up against one another. This makes them appear more grounded and solid. So, blocking in the inbetween forms will help you better understand how they're all meant to fit together, while also saving you from neglecting an entirely important part of the body. Which is... the rest of it. Here's an example of what I mean, on another student's work.

When it comes to feet, here's an approach you can try to apply (again, notes on another student's work). I can see that you do often vary your approach when tackling feet, sometimes trying to capture more all at once than you should, resulting in more complex shapes/forms. This approach will help you continue to tackle them in a step-by-step, constructional fashion.

The last thing I wanted to discuss is head construction. Lesson 5 has a lot of different strategies for constructing heads, between the various demos. Given how the course has developed, and how I'm finding new, more effective ways for students to tackle certain problems. So not all the approaches shown are equal, but they do have their uses. As it stands, as explained at the top of the tiger demo page (here), the current approach that is the most generally useful, as well as the most meaningful in terms of these drawings all being exercises in spatial reasoning, is what you'll find here on the informal demos page.

There are a few key points to this approach:

-

The specific shape of the eyesockets - the specific pentagonal shape allows for a nice wedge in which the muzzle can fit in between the sockets, as well as a flat edge across which we can lay the forehead area.

-

This approach focuses heavily on everything fitting together - no arbitrary gaps or floating elements. This allows us to ensure all of the different pieces feel grounded against one another, like a three dimensional puzzle.

-

We have to be mindful of how the marks we make are cuts along the curving surface of the cranial ball - working in individual strokes like this (rather than, say, drawing the eyesocket with an ellipse) helps a lot in reinforcing this idea of engaging with a 3D structure.

Now the thing is, you are doing this to varying degrees in a lot of cases. I wanted to lay this out however simply because it can often help to push students to follow that approach more closely, and to get a more specific sense of what is most important about the approach. Sometimes it seems like it's not a good fit for certain heads, but with a bit of finagling it can still apply pretty well. To demonstrate this for another student, I found the most banana-headed rhinoceros I could, and threw together this demo.

And that about covers it! There's plenty of things you can certainly improve upon, and I imagine you will with practice as you try to apply what I've shared here, but as a whole, I am pleased with your progress. I'll be marking this lesson as complete without any further revisions.

Next Steps:

Move onto the 250 cylinder challenge, which is a prerequisite for lesson 6.

6:12 PM, Saturday July 9th 2022

Thanl you for the feedback, it was very helpful. I will be sure to focus on the points you described.

PureRef

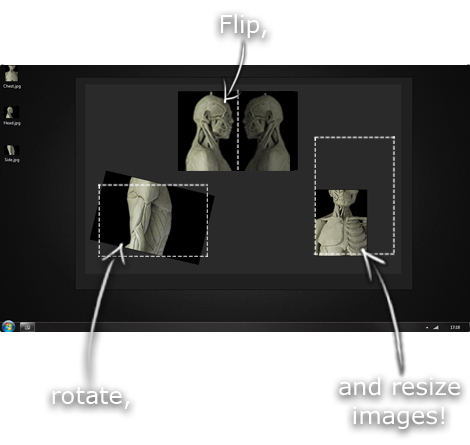

This is another one of those things that aren't sold through Amazon, so I don't get a commission on it - but it's just too good to leave out. PureRef is a fantastic piece of software that is both Windows and Mac compatible. It's used for collecting reference and compiling them into a moodboard. You can move them around freely, have them automatically arranged, zoom in/out and even scale/flip/rotate images as you please. If needed, you can also add little text notes.

When starting on a project, I'll often open it up and start dragging reference images off the internet onto the board. When I'm done, I'll save out a '.pur' file, which embeds all the images. They can get pretty big, but are way more convenient than hauling around folders full of separate images.

Did I mention you can get it for free? The developer allows you to pay whatever amount you want for it. They recommend $5, but they'll allow you to take it for nothing. Really though, with software this versatile and polished, you really should throw them a few bucks if you pick it up. It's more than worth it.