This website uses cookies. You can read more about what we do with them, read our privacy policy.

3:33 AM, Friday May 7th 2021

Starting with your organic forms with contour lines, you're definitely making an effort to stick to the characteristics of simple sausages, and that certainly shows. There are two main issues I'm seeing however:

-

When drawing your contour ellipses, it appears that you're not shifting the degree of your contour ellipses. I can see you doing that somewhat with contour curves (although it's more that you're just allowing them to reverse - you otherwise seem to still stick to the same degree rather than letting them progressively get wider or narrower). I explain why the degree of your contour lines will shift in the more recently updated ellipses video for lesson 1.

-

In your page of organic forms with contour curves, you place that little contour ellipse on the ends (which is good), but you place them on the wrong ends much of the time, which suggests that you're not actually aware of, or thinking about, what they're meant to represent. Ellipses and curves, they're all basically the same thing - a contour line that runs along the surface of the form. When the tip of a sausage form points towards the viewer, the whole ellipse becomes visible, otherwise we only see a partial curve. You however tend to draw them on the ends that, based on all the other contour lines, are facing away from the viewer. Here are some examples of different sausage forms - with one end pointing towards the viewer, both ends pointing towards the viewer, and no ends pointing towards the viewer. Hopefully that should clarify what I mean.

Moving onto your insect constructions, there's one very important point I want to call out - you tend to draw pretty small. When we draw small and specifically limit the room we have for a given construction, we impede both our brain's spatial reasoning skills, and make it harder to engage our whole arm while drawing. This results in clumsier constructions and linework, and can cause us to make a lot of mistakes that we might not have otherwise.

It is critically important that you give each drawing as much room as it requires, first and foremost. It's good to want to fill your pages with drawings, but to be fair, you didn't do that either - there were plenty of pages where you could have included more insect drawings the same size as the others that were there, but you opted not to do that either. It seems like you were being rather arbitrary about it.

Instead of however you made your decision of how big to draw, or how many individuals to draw, focus first on drawing the first thing on a page as big it really demands of you. Focus on engaging your whole arm from the shoulder, and really establishing those simple forms as you build your way up to greater levels of complexity. Then when you're done, assess whether there's more room to fit another drawing. If there is, great - draw another and repeat the process until there isn't any left. If there isn't, that's fine too - as long as the space is put to good use, it's okay to end up with some pages with just one drawing.

So this is the biggest issue - it's resulting in a lot of oversimplification, and is probably going somewhat hand in hand with you not necessarily spending enough time observing your reference images. Remember that you need to be looking at your reference images almost constantly, looking away only long enough to construct a specific, enclosed form. From what I can see, the drawings where you draw small and cramped, you also seem to look at your reference less.

Moving on, the next point I wanted to call it out is that because we're drawing on a flat piece of paper, we have a lot of freedom to make whatever marks we choose - it just so happens that the majority of those marks will contradict the illusion you're trying to create and remind the viewer that they're just looking at a series of lines on a flat piece of paper. In order to avoid this and stick only to the marks that reinforce the illusion we're creating, we can force ourselves to adhere to certain rules as we build up our constructions. Rules that respect the solidity of our construction.

For example - once you've put a form down on the page, do not attempt to alter its silhouette. Its silhouette is just a shape on the page which represents the form we're drawing, but its connection to that form is entirely based on its current shape. If you change that shape, you won't alter the form it represents - you'll just break the connection, leaving yourself with a flat shape. We can see this most easily in this example of what happens when we cut back into the silhouette of a form.

While you do this to varying degrees, the most obvious case of it is the upper-left drawing on this page where you start with a larger ball form (though you're probably thinking of it more as an ellipse rather than a 3D form), and then you cut back into it as needed. If we look at the insect below it, the one with all the spikes, that's an example of where we're doing something quite similar - extending the silhouette with flat shapes. Either way, you're working in 2D space, not treating your constructions as though they're 3D.

Instead, whenever we want to build upon our construction or change something, we can do so by introducing new 3D forms to the structure, and by establishing how those forms either connect or relate to what's already present in our 3D scene. We can do this either by defining the intersection between them with contour lines (like in lesson 2's form intersections exercise), or by wrapping the silhouette of the new form around the existing structure as shown here.

You can see this in practice in this beetle horn demo, as well as in this ant head demo.

This is all part of accepting that everything we draw is 3D, and therefore needs to be treated as such in order for the viewer to believe in that lie.

The last thing I wanted to call out for now was in terms of how you treat the detail phase of your drawings. Right now it appears that when you feel you're done construction and decide to get into adding detail, your goal shifts primarily to that of decoration - that is, making your drawings look nice and impressive, to add as much as you can to them to create a sort of "wow" factor. The problem with that is that it's not a very concrete target - it's much more subjective and general, and therefore harder to work towards.

What we're doing in this course can be broken into two distinct sections - construction and texture - and they both focus on the same concept. With construction we're communicating to the viewer what they need to know to understand how they might manipulate this object with their hands, were it in front of them. With texture, we're communicating to the viewer what they need to know to understand what it'd feel like to run their fingers over the object's various surfaces. Both of these focus on communicating three dimensional information. Both sections have specific jobs to accomplish, and none of it has to do with making the drawing look nice.

Now, I'm going to assign some revisions below for you to apply what I've called out above. If you feel you can, try to spend more time on each individual drawing. Remember that there's no deadline or specific speed you need to be able to work at. If you can't get a drawing done in one sitting, that's okay too - you can always spread them across multiple sessions and days if needed. The only thing that matters is that you execute each mark to the best of your ability, and push each drawing to its furthest. There are definitely a lot here that felt lacking in that regard, like they weren't getting all of your attention or energy.

Next Steps:

Please submit the following:

-

1 page of organic forms with contour curves

-

3 pages of insect constructions

11:51 PM, Tuesday May 18th 2021

3:46 PM, Thursday May 20th 2021

Your drawings are moving in the right direction, but there are definitely signs that you are not completely understanding the critique I provided previously, at least not in its entirety. Here I've marked out three major issues.

Most significantly, you blocked in your abdomen with a simple form, then cut back into its silhouette in precisely the manner you were told not to, in order to change it. If you find that your construction doesn't match your reference image, it's too late to make those big changes. Accept the direction your construction has taken, and keep going. The result of you trying to change it instead was to add massive contradictions to what your viewer sees, undermining their suspension of disbelief.

There are also a number of places where you didn't draw each form in its entirety. Remember that construction is about adding new, complete, three dimensional forms to your structure. Any situation where you just add a flat shape (for example, when you allow the forms you draw to get cut off on one side when they're overlapped by something else) will remind the viewer that they're looking at a drawing rather than a real object.

I didn't call this one out in your original submission, but it's also important that you adhere closely to the sausage method. You're definitely applying it in a number of places, and I get the impression that you are trying to use it across the board, but that you're just a little too relaxed in how you approach it. That diagram shows three key points that need to be adhered to:

-

Your segments should each adhere to the characteristics of simple sausages (two equally sized spheres connected by a tube of consistent width. Keep the ends circular, avoid stretching them out, and don't have the midsection get wider or narrower.

-

The segments should overlap/intersect visibly.

-

The joints between those segments should be defined with a contour line.

The key to keep in mind here is that the sausage method is not about capturing the legs precisely as they are - it is about laying in a base structure or armature that captures both the solidity and the gestural flow of a limb in equal measure, where the majority of other techniques lean too far to one side, either looking solid and stiff or gestural but flat. Once in place, we can then build on top of this base structure with more additional forms as shown here, here, in this ant leg, and even here in the context of a dog's leg (because this technique is still to be used throughout the next lesson as well). Just make sure you start out with the sausages, precisely as the steps are laid out in that diagram - don't throw the technique out just because it doesn't immediately look like what you're trying to construct.

I do think you're moving in the right direction, but that massive example of cutting back into your silhouettes is a real problem. I'm going to assign another 3 insect constructions as revisions. To get another couple of examples of how you should be approaching your constructions, take a look at the shrimp and lobster demonstrations at the top of the informal demos page.

Next Steps:

Please submit an additional 3 insect constructions.

9:54 PM, Monday May 24th 2021

http://imgur.com/gallery/9ZhPrrr

here is your army of insects.

PureRef

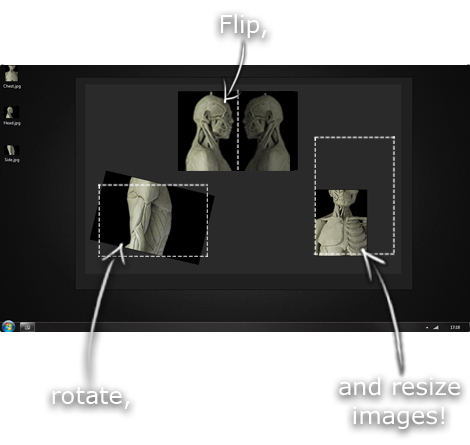

This is another one of those things that aren't sold through Amazon, so I don't get a commission on it - but it's just too good to leave out. PureRef is a fantastic piece of software that is both Windows and Mac compatible. It's used for collecting reference and compiling them into a moodboard. You can move them around freely, have them automatically arranged, zoom in/out and even scale/flip/rotate images as you please. If needed, you can also add little text notes.

When starting on a project, I'll often open it up and start dragging reference images off the internet onto the board. When I'm done, I'll save out a '.pur' file, which embeds all the images. They can get pretty big, but are way more convenient than hauling around folders full of separate images.

Did I mention you can get it for free? The developer allows you to pay whatever amount you want for it. They recommend $5, but they'll allow you to take it for nothing. Really though, with software this versatile and polished, you really should throw them a few bucks if you pick it up. It's more than worth it.